This is a two-parter. First is about Passover. If you want to skip it, you can go right to Education in Nicaragua.

The Forgetting of Elvin Hayes

I went to a family seder last night in Highland Park--not my family's. It was presented to me as a full-bodied thing, with lots of singing, and it was. I was the odd person out. I came by myself, but there were place cards, so I got to sit by the hostess. L opted not to go; he was traumatized by his bar mitzvah and avoids ritual as much as possible. We went to B & S's seder on Monday, for which L gave up watching the Florida-OSU game in real time. (He recorded the game with our neighbor Z's TiVo to watch after the seder. We won't talk about how during the meal X announced the score at the end of the second half.) I have long had an image in my mind of the seder of my dreams. It's like a class of my dreams. Everyone is smart and engaged and wants the reading and discussion to go on and on. Our family has never had seders like that. They can't be coerced. They aren't big singers. My aunt was a good singer but she died. My other aunt's second husband was a good singer but when my aunt died he went elsewhere for seder. My father was an off-key but enthusastic singer, but he died. His rendition of Khad Gadya, one of the songs at the end, sounded like a football cheer in Hebrew with Yiddish pronounciation. I have not heard the like of it since. This generation of children is quiet and not show-offy. You need people with bluster to carry songs all the way through. They say that cantors are frustrated opera singers. We need frustrated Broadway musical actors at our seders.

The seders I lead are big, maybe 25 people, and the people are usually sitting at five different tables. That makes it hard for discussion. For a while we would go around and say who we missed, but then it got too sad. At the end of the service, we say, Next year in Jerusalem. Meaning, next year perfection. In that spirit, we've written wishes on index cards and then read wishes written and saved from the year before. That got too sad, too. Then we'd talk about Passover memories, but they were mostly generic. I wrote a series of "I remember"s, linked to different eras, such as: I remember how hot my the soles of my feet would get when we were walking in the desert.... I remember blisters all over my hands from the bricks for the Egyptians... OK, I can't think of any of my better examples. I would pass these out to everyone, and each person would read a different one aloud. Was this meaningful to my constituents? I don't know. Was it just an exercise in literary ego?

I started leading the seder in the first place when I encountered an egalitarian haggadah written by Aviva Cantor and published in her magazine, Lilith. My father let me incorporate it into his service, which used a pre-war Reconstructionist haggadah and featured illustrations of androgynous men wearing loose shifts. I don't remember when this was, but by 1990 I had photocopied haggadahs for everyone, using several elements and probably violating several copyrights. What was nice about the book haggadahs was the leader (my father, and before him, his father) would make notes, so you would see, next to the Mah Nishtanah, said by the youngest child, the name of my aunt who was now very much an adult.

I've been looking for years for new information and readings to include, and this is the secret--there's not much out there. Yes, there are ideas for acting out scenes from the exodus; there are songs about the plagues that God brought on the Egyptians ("Frogs frogs frogs") and a song about the four sons, to the tune of "Clementine"; there are passages that describe the important role of midwives Shifra and Puah, and of Moses' sister, Miriam; there are questions meant to be thought-provoking, like: What are some modern plagues?; there are haggadahs that talk about Israel's guilt in Sabra and Shatilah; you can talk about the Warsaw Ghetto and sing the partisan fight song; there are prayers re-written to include the feminine aspect of God--but the truth is, most haggadahs are the same. They tell the same story, about the Jews coming into Egypt, and being enslaved there, and being led out by God, and becoming thusly a people with a land. There are many things to talk about, but you can't force discussion. Our most heated discussion Monday night came after dinner, when we were trying to figure out who the Maccabees had fought against (I know, wrong holiday). The dinner guest to my right, a half-Jewish, atheist high school senior in a Catholic school, had perceptive anti-religious barbs to deliver, which we all agreed with. She was used to challenging the nuns. How can you engender a discussion in which everyone has something at stake? I don't feel like "sharing" what I feel enslaved to in my personal life, or listing, condescendingly, the golden calves of America. I don't feel like naming Jewish women I admire. (An aside: At a seder two years ago, in response to this request for naming, my Republican cousin said, Condoleeza Rice.) To me, the inescapable question is, Why are we here? but that may not be so relevant after all.

At the family seder last night, our leader was like a good teacher. We read through the service and he would offer tidbits now and then. That every time there's a pivotal point in the Bible, there's a woman. There's a famous paragraph in the haggadah in which five rabbis are mentioned. This paragraph usually falls, by chance, to a young reader who stumbles over all their names. We are told that they stayed up all night discussing Passover. This is an object lesson for the rest of us, who've been through the story dozens of times: Even the greats found something to discuss. They were splitting hairs, such as debating whether "all the days of your life" included the nights, both actual and metaphorical. Another interpretation of their all-nighter is that they were staying up to plan the Bar Kochba rebellion (132-135 CE) against the Romans, who were oppressing the Jews. What our leader did last night was tell a little about each of these guys we'd been naming every year. Rabbi Tarfon, for example, was famous for saying, "It is not your job to finish the task, nor are you free to avoid it all together." And another was known as the last holdout to favor making chicken pareve.

Each family has its own ways of doing things and I missed our ritual of reciting a counting song, "Who Knows One?" in English. Everyone tries to say the last paragraph about numbers 1-13 in one breath. This family sang it in Hebrew, and kept going faster and faster with each added number. I also missed singing "Elvin Hayes" instead of "El b'nai" in the chorus to "Adir Hu." This year I realized that you could also substitute "Karl Rove" for "beka'arov" in the chorus. I will have to tell my people next year.

As I'm writing this I'm going through my store of haggadahs and sifting through the Internet. And I'm finding that information does matter. I disagree with what I said a few paragraphs up.

(Do I contradict myself? Very well, then, I contradict myself.) For example, I'm re-reading the Jewish Labor Committee's haggadah and finding a story about the moment the Jews were leaving Egypt and the Pharoah's army was charioting right behind them. In this story, the Red Sea did not divide right away. The Jews panicked. Then one guy, Nachshon, waded in, almost up to his neck. He kept the faith--and the waters parted.

I'm also thinking that discussion might not be necessary. Last night there was some back-and-forth but I wasn't champing at the bit to make one point or the other. Have I longed for *robust* (the current buzz word) discussion from my people as proof that they were listening? Maybe they were listening quietly all these years. It can be enough to learn something interesting. Dayenu.

Education in Nicaragua, 1989

Inflation made the value of the currency change at least every week. Every week a bus token cost more. I have still one piece of Nicaraguan paper money with three zeroes added on, printed officially by the national bank. The electric grid was unstable. It wasn't unusual for the lights to go out in the middle of class. Our room didn't have any windows. There would be certain days when we didn't have running water. Water service was rotated by neighborhood. The night before the water wasgoing to be cut off, we would fill up barrels with water. The plumbing wasn't so great to begin with. You weren't supposed to flush anything, even toilet paper. There was a wastebasket next to each toilet for you to drop your used paper. And you'd need to provide your own toilet paper. This was in the capital city. It had buses that worked, though they were always filled beyond capacity and it was ordinary for young boys to hang from the outside of the bus. There were pay phones, or at least places where there had been pay phones, but every part of the apparatus had been stripped. I could never figure out where I was or how to get anywhere. The street names were informal and most were hand-written signs, named after the local resident who had died with the revolution. My address was something like: three blocks north of the Esso station, a block from where the baobab tree used to be. There were cabs, but for some reason a driver would not turn around. You had to be going in the same direction as the cab. I was teaching English to government health workers, lab technicians with the equivalent of a master's degree and nearly starvation wages. There weren't any photocopying machines. I'd brought my own exercises with me and just went by feel. Everyone was at a different level. The previous teacher, I'd been told, had drilled them on verbs. I'd been told in a way that made me feel I should do the same. So I did some time, or I would help them translate English instructions that came with a machine or instrument, or ask them what they had trouble understanding. They asked me how to pronounce "grocery" and weren't satisfied because they expected a three-syllable British pronunciation. I taught the most advanced student the phrase, I have a time conflict, then wondered if that was idiomatic enough. He grew very attached to that sentence. One day I went to the bathroom at work, and started to toss my used paper in the trash. In the wastebasket I saw something there that looked familiar; it was an exercise from a few days before. I said to myself, At least I know that the handout was useful.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

taramosalata & other dips; photo by Vera Szabó

cream puffs, caprese; photo by Vera Szabó

Don't try this at home. Uh, oh, we did.

L the Haircutter in Background

Finished.

design by Jennifer Berman

At medicinal baths, with testimonials from patients

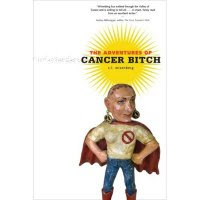

One Feminist's Report on Her Breast Cancer, Beginning with Semi-diagnosis and Continuing Beyond Chemo, w/ a side of polycythemia thrown in **You don't have to be Jewish to love Levy's rye bread, and you don't have to have cancer to read Cancer Bitch *** Cancer Bitch comes to you from S.L. (Sandi) Wisenberg in Chicago

Click on photo for Cancer Bitch reading/lecture schedule

Blog Archive

-

▼

2007

(192)

-

▼

April

(23)

- Cancer Bitch Behaves Badly Again

- Remembrance of Things Past or: Everybody's Got a W...

- A Cancer Bitch Behaving Badly

- Freedom and Development

- Notes on the Visible/Invisible

- Cancer is Boring

- Head Covering

- Men with Guns 2

- Men with Guns

- When It Falls, It Falls

- The End of Women and Children First???

- Briefly

- Hair is a Woman's Crowning Glory

- The Government Knows Much

- The Neighborhood Internist & An Embarrassment of G...

- The Neighborhood Acupuncturist

- The Forgetting of Elvin Hayes & Education in Nicar...

- Passover--First Day--Hasids

- The Fifth Question

- Go, Cancer Bitch, Go

- My Most Useful Teaching Moment

- El Repliegue

- Two Miles

-

▼

April

(23)

Cancer Bitch recommends these links:

- Alternet.org

- As the Tumor Turns

- Being Cancer--its on-line book club discusssed my book.

- Big Grrls DO Cry: queer life meets precarious life

- Black Gyrl Cancer Slayer

- Breast Cancer Action

- breastcancer.org

- Chemo Chicks

- Chronic (Illness) Babe

- Code Pink women's peace group

- Collaborative on Health and the Environment

- Colon cancer cowgirl

- Earth Henna

- Friends of Cancer Bitch on Facebook

- Funny Cancer shirts and mugs

- Gayle Sulik, Pink Ribbon Blues

- Geezer Sisters (tho' only written by one of them)

- Get Real About Breast Cancer (w/ pic of Breast Cancer Barbie)

- Gilda's Club

- Goodbye to Boobs (by a pre-vivor)

- Humerus Cartoons

- I got the cancer (lymphoma)

- Mamawhelming

- Organic Consumers Assn.

- Our Bodies, Our Blog

- Paula Kamen

- Planet Cancer

- Recovery on Water

- S.L. Wisenberg/Red Fish Studio

- Skin Deep: un/safe cosmetic list

- Stacey Richter's Land of Pain

- Swimming in the Trees: author Jessica Handler of Atlanta

- Tara Ison

- Terry Tempest Williams

- The Assertive Cancer Patient

- The Cancer Culture Chronicles

- The Fifty-Foot Blogger, another denizen of Fancy Hospital

- Whirled News--better than the Onion

- Women & Children First bookstore

NOTATE BENE

Everything here is as accurate as I could make it. Occasionally I've changed identifying details when writing about others.

Links to audio and video

from my Farewell to My Left Breast party

taramosalata & other dips; photo by Vera Szabó

Farewell to My Left Breast Party

cream puffs, caprese; photo by Vera Szabó

April 12, 2007--The Making of the Mohawk

Don't try this at home. Uh, oh, we did.

The Mohawk Profile

L the Haircutter in Background

The Mohawk Demure

Finished.

Summer henna-wear

design by Jennifer Berman

Life after cancer, Budapest, July 2009

At medicinal baths, with testimonials from patients