God help us! I just watched Showtime's

The Big C online while sitting in my bed and breakfast room on State Street in downtown Jackson, Mississippi. It's funny. It's ironic. It's sardonic. It's clever. It's cute.

It's unrealistic. It's demeaning. It delivers a very very odd message about race.

It begins with a black guy from the swimming pool company talking to the blonde (Laura Linney) about how unrealistic a pool is for her yard. We are in Minneapolis but we could be anywhere where there are driveways and shrubs and lawns and single-family dwellings that one can afford to expand. He says instead she should "bump out the deck," put in a hot tub and and barbecue pit. To get it done faster, she offers to pay him double. OK, I'll start tomorrow, he says. (Later she decides she does want the pool no matter what, and he says he'll get a digger tomorrow. "The bigger the digger the better," she quips. Ugh. Insert joke here about black men and their big diggers.)

It ends with Linney talking to someone who's off-camera: therapist? husband? No, ha ha. It's a dog. I think it's the neighbor's basset hound. And it's unclear whether he's listening. Then as the camera goes further and further away, we see them on the couch together, isolated as if in a boat, and then the

FUCKING CIVIL RIGHTS ANTHEM, "This Little Light of Mine" plays.

What is going on here?

Race relations are un-problematized. Cancer is de-clawed. She might as well start singing, I Feel Pretty. She sure looks pretty. Healthy.

But Cancer Bitch, didn't you say you feel fine till the treatment starts?In between we have Linney telling her handsome young Indian-looking doc (he's 31, she's his first terminal patient, lotta yucks about being the first) all about her swimming games as a kid while she's in the exam room, and then they meet for a meal. Maybe this is how they do medicine in Minnesota, but ain't never seen nothin' like that in Chicago, and, like Linney's character, I too have health insurance.

This seems to be a fantasy about what happens when you say what you've been swallowing all this time. She tells her fat, mouthy black student: "You can't be fat and mean." Linney tells the girl that the other kids laugh at her cruel jokes, but nobody's asking her to the prom. And at their next encounter, Linney offers the girl $100 for every pound she loses as long as she quits smoking. Seems like we're getting pretty close to the territory of Blame the Victim for Her Cancer--she was repressed, so see what happened!

She finds out her neighbor has complained about the backyard construction so walks straight into the old biddy's house and accuses, "You have never smiled even a little bit." And the old lady's house and lawn are a mess, too.

Of course, because this is TV-land, next time we see them the neighbor has upswept her hair, cross the street to shake hands, and smiles and asks to borrow the lawnmower.

And because this is TV, and because everything is so funny haha, her husband hears her doctor's compassionate message on the phone and assumes she's having an affair. She doesn't tell anyone--her son, her husband, her save-the-world goofy brother--that she's got metastatic cancer.

"It makes me feel better to think we're all dying," she says (to the dog). Profound. Never thought of that before. I'm here all year, she says. Performing at stage four. (That was a clever line. Really.) "The laughter might turn into a sob in a second." And it does.

So next episode, we'll be wondering, Will she tell or won't she? Will she mention money? Will cancer be anything more than a giant wake-up call? And at the end, will she be able to best Oscar Wilde's final line: "My wallpaper and I are fighting a duel to the death. One or the other of us has to go"?

And what is it about Hollywood and house expansion? That disappointing movie with Meryl Streep in it centered around the Steve Martin architect character who came into her life to expand her house. After her second and last kid left for college. Isn't that a sign that it's time to downsize?

Note to Hollywood: Can you spell F-o-r-e-c-l-o-s-u-r-e?

***

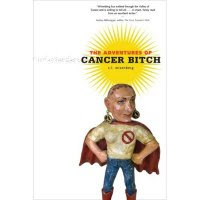

Hey, kids, here's

someone who died from

breast cancer, as well as other stuff!