The other day I stopped in at B & S's house and brought in the mail. B asked me to open the plastic wrapper that Poetry magazine had come in. Before I handed it to him I looked on the back for the authors this month and read off names I recognized. B took it and read off more names. He's a poet, so of course he'd know more of his ilk. He said, You gave up journalism for Art. Which was a nice way of saying things and isn't entirely true. It wasn't a conscious decision. I can be slow to realize what the common wisdom is--about anything. I didn't realize for years that many people think of fiction as Art, and journalism as Lesser Non-Art. For undergrad I went to J-school, and then to Famous Creative Writing School, where I'd questioned the purpose of Art when Reagan had his finger on the button and the budget. I would travel to Des Moines and Milwaukee and DC and New York City to protest nuclear proliferation and draft registration. I thought journalism was the highest and best you could aspire to because it Did Something, especially investigative journalism, which, by the way, I wasn't doing. I was writing features. But some of them had a socially-useful aspect. OK, some of them.

A friend of mine, N, taught a course on journalism that changed society, using books as texts. When student complained to her and her boss that N had assigned too much reading, she didn't back down. She decided the next year to add more required reading. She's tenured.

In graduate school I discovered radical philosophers on art and society and almost created an independent study for myself on political novels. I don't remember why I didn't follow through. When I worked for the major newspaper after grad school, someone in the newsroom said as if it were an acknowledged fact, that the novel was the real writing, not journalism, and I was mystified. I may still be. While at the same time, when I heard a major historian talk about the numbers of men who become cold mass killers in certain situations, I thought about William Carlos Williams' short story, "The Use of Force," which shows that the most humanitarian intentions can lead to violence and corrode the soul.

Reach for an L Instead of a Pill

There was an ad for cigarettes, relying on at vanity: Reach for a Lucky instead of a Sweet. Yesterday I told L all about my anxiety about working on my book. I mean, I tell him about most of my anxieties but hadn't told him just how terrible I'd been feeling, worrying about revising my book and also about buying this house. He told me that I always get like this before a big deadline. It always helps when he tells me things like this. Then it means that the horrible feeling will end. And it did. So I didn't need to take an Ativan.

Today I decided to go over two theses I needed to for thesis meetings on Saturday. I thought after going through student work I'd feel eager to go back to my own. I made it through one and half theses. The second one contains stories I've read about five times, in different versions, and instead of being sick of them, I felt comforted in their familiarity. I keep searching for the right simile for this experience, or analogy. I feel that each time a person reads a story, the reader re-animates the characters, takes them off the shelf, turns the key in the back of the toy. Adds water to sea-monkey packet. And when you read a story for the nth time, everything in it is just etched a little deeper in your brain, joining the other images you had stored there from when you read the story before. Maybe what I mean is that everything you read in the past becomes a memory, and when you read the story again, the images and characters you imagine in the present join up with your memories of the images and characters, and the story seems more real because of the memories. And to complicate it all, there are the ghosts of the past drafts, hovering, shadowy--the roads the writer took and back-tracked. As they say, Don't think of a white bear.

I was going through the theses in the Little Cafe, and I wanted to take a break, so I reached for one of the New Yorkers I'd donated to the cafe in order to clear out my house. I read an article about the changes Gordon Lish made to Raymond Carver's stories. I assume this is old news for everyone who reads their New Yorkers when they arrive. Or for anyone who read D.T. Max's article in the New York Times in 1998. So then I read "Beginners" in the New Yorker, which became "What We Talk About When We Talk About Love." A few hours later I read the latter, which Lish had shortened very much. Of course the shadow of the longer story was in my head as I read the shorter version. I was wondering about the best way to present the two versions to a fiction class. (People have long compared two versions of Carver's story "Cathedral.") Do you have the students read the uncut story first or the shorter version? Maybe have half the class read the shorter first, and the other half, the opposite. And have them debate which is better.

Carver wrote to Lish in panic and distress, telling him not to publish his collection as Lish had edited it, because so many people had read his drafts and would realize how much Lish shaped his work. A couple of days later he was mollified, presumably after talking on the phone with Lish.

Carver has been dead 20 years. Lish is still alive. In a thesis meeting last week a student reminded me that I'd written the punchline at the end of a paragraph. I didn't remember suggesting it. But I thought it was funny.

I still cringe when I think about an edit I did in fifth or sixth grade. We had a class newspaper paper and a guy named Bert Parker wrote a paragraph about guns or hunting and said something would be painful. I inserted "excruciatingly."

Today I decided to go over two theses I needed to for thesis meetings on Saturday. I thought after going through student work I'd feel eager to go back to my own. I made it through one and half theses. The second one contains stories I've read about five times, in different versions, and instead of being sick of them, I felt comforted in their familiarity. I keep searching for the right simile for this experience, or analogy. I feel that each time a person reads a story, the reader re-animates the characters, takes them off the shelf, turns the key in the back of the toy. Adds water to sea-monkey packet. And when you read a story for the nth time, everything in it is just etched a little deeper in your brain, joining the other images you had stored there from when you read the story before. Maybe what I mean is that everything you read in the past becomes a memory, and when you read the story again, the images and characters you imagine in the present join up with your memories of the images and characters, and the story seems more real because of the memories. And to complicate it all, there are the ghosts of the past drafts, hovering, shadowy--the roads the writer took and back-tracked. As they say, Don't think of a white bear.

I was going through the theses in the Little Cafe, and I wanted to take a break, so I reached for one of the New Yorkers I'd donated to the cafe in order to clear out my house. I read an article about the changes Gordon Lish made to Raymond Carver's stories. I assume this is old news for everyone who reads their New Yorkers when they arrive. Or for anyone who read D.T. Max's article in the New York Times in 1998. So then I read "Beginners" in the New Yorker, which became "What We Talk About When We Talk About Love." A few hours later I read the latter, which Lish had shortened very much. Of course the shadow of the longer story was in my head as I read the shorter version. I was wondering about the best way to present the two versions to a fiction class. (People have long compared two versions of Carver's story "Cathedral.") Do you have the students read the uncut story first or the shorter version? Maybe have half the class read the shorter first, and the other half, the opposite. And have them debate which is better.

Carver wrote to Lish in panic and distress, telling him not to publish his collection as Lish had edited it, because so many people had read his drafts and would realize how much Lish shaped his work. A couple of days later he was mollified, presumably after talking on the phone with Lish.

Carver has been dead 20 years. Lish is still alive. In a thesis meeting last week a student reminded me that I'd written the punchline at the end of a paragraph. I didn't remember suggesting it. But I thought it was funny.

I still cringe when I think about an edit I did in fifth or sixth grade. We had a class newspaper paper and a guy named Bert Parker wrote a paragraph about guns or hunting and said something would be painful. I inserted "excruciatingly."

Update

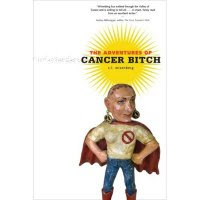

Cancer Bitch is afraid she will get her blogger award stripped from her because she hasn't blogged in ever so long. She is working hard revising the manuscript based on this blog. It's due at University of Iowa Press June 1 and she is ever so anxious about it. She has had a lump in her throat for about 10 days and takes Ativan for it from time to time and then gets anxious she will become addicted. She is also in the midst of buying a house and quakes at the prospect of actually living full-time with her husband. Right now they live together most of the time in her condo, where 95 percent of the furniture and Stuff is hers. He has half a (big) closet and two dressers and half the bathroom. The rest is in his house in Gary, which he'll sell next spring. But he dislikes most of her furniture and pictures and she doesn't like his pictures so much and she thinks he hangs them too close to the floor anyway. Everything is overwhelming though she knows that in the grand scheme of things these problems are but fly specks. She wonders if any of her readers have anything to say about the New York Times magazine story about blogging and becoming Known. She understands the author's tendency to "overshare" and her feeling that her life is public and private at the same time. But didn't Jennifer Weiner mine some of this same territory in Good in Bed? The NYT story is very thin on cultural history, or any history not the narrator's own. There are no references to other tell-alls, except one that unfolded right as hers did: "For a few hours, my personal dramas took a backseat — sort of — to news that a Pulitzer-winning author had described his wife’s affair with a media mogul in a crazy e-mail message to his graduate students." But what do you expect from a piece that begins "Back in 2006..."?

Is C. Bitch being too harsh? Perhaps. It may be too much to expect a confession to provide cultural and political perspective about a phenomenon while the author is in the middle of it. Mostly, she is amazed at how quickly someone can become famous. But in this day and age, she shouldn't be surprised.

Is C. Bitch being too harsh? Perhaps. It may be too much to expect a confession to provide cultural and political perspective about a phenomenon while the author is in the middle of it. Mostly, she is amazed at how quickly someone can become famous. But in this day and age, she shouldn't be surprised.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)