The Four Questions are asked on Passover, beginning with, Why is this night different from all other nights? which is also the punchline of a joke about Sir Lancelot.

The fifth question is how and why we celebrate the holiday if we do not believe in the historicity of it, that we were slaves in Egypt, and if we do not believe in a diety; if we do not put any credence in the central covenant we read about on Passover, the covenant with God—that He told Abraham I will make your people slaves but after 400 years I will liberate them and they will be a great nation. That as the result of the torture of the tribe, they will emerge a cohesive group and they will have a land of their own. This is the same lesson that some people draw from the Holocaust: The Jews were tortured and burned in Europe and now they emerge, liberated with a land of their own.

It has been said that modern Jewish practice is ancestor worship. We put on this ritual and set this table and bake this kugel because bubbe did it. We take a little bit of the tam, the taste, of the holiday and swish it in our mouths a bit, and wait for the memories to blossom, Proust-like. Proust was Jewish but I don’t know where his Jewishness lay. Or half-Jewishness. The New York Times years ago had an article about Passover macaroons, quoted a Jewish baker saying the canned ones set off Proustian associations.

I always wanted a seder where people argued and discussed and we did both tonight. But we did not get to the answer to the central questions: What does this mean? Why are we here? What do we do about the readings that we don’t like? Why is the father so harsh when he tells his child that he wouldn’t be taken out of Egypt because he doesn’t consider himself part of the tribe? We laugh at him and then we turn the page.

The story is true, says the chancellor of the Jewish Theological Seminary, even if it didn’t happen, just as great literature is true. The exodus is one of our central myths. Our daily prayers (if we were to say them) mention being taken out of Egypt. I have read more than a dozen haggadahs that try to make the story and the holiday relevant. If you do not believe, you have to think your way around so much. You have to change the donne’ of every haggadah and say, There is a story that our people have told, and it is not historic. Yet it has great meaning for our people and it has mythic structure. You have to qualify everything.

And after you’ve qualified everything, you say, This is a holiday in my bones and blood, its cadences are driven into me. And that’s why I’m here. And while I’m here on a purely emotional level, that is the reason for my return, I want to get some intellectual and moral sustenance. But all that is so much work. But to not do that is to be reduced to the level of a child absorbing a fairy tale without question, because it’s so familiar.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

taramosalata & other dips; photo by Vera Szabó

cream puffs, caprese; photo by Vera Szabó

Don't try this at home. Uh, oh, we did.

L the Haircutter in Background

Finished.

design by Jennifer Berman

At medicinal baths, with testimonials from patients

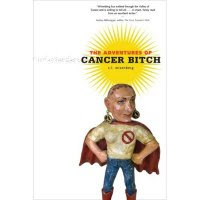

One Feminist's Report on Her Breast Cancer, Beginning with Semi-diagnosis and Continuing Beyond Chemo, w/ a side of polycythemia thrown in **You don't have to be Jewish to love Levy's rye bread, and you don't have to have cancer to read Cancer Bitch *** Cancer Bitch comes to you from S.L. (Sandi) Wisenberg in Chicago

Click on photo for Cancer Bitch reading/lecture schedule

Blog Archive

-

▼

2007

(192)

-

▼

April

(23)

- Cancer Bitch Behaves Badly Again

- Remembrance of Things Past or: Everybody's Got a W...

- A Cancer Bitch Behaving Badly

- Freedom and Development

- Notes on the Visible/Invisible

- Cancer is Boring

- Head Covering

- Men with Guns 2

- Men with Guns

- When It Falls, It Falls

- The End of Women and Children First???

- Briefly

- Hair is a Woman's Crowning Glory

- The Government Knows Much

- The Neighborhood Internist & An Embarrassment of G...

- The Neighborhood Acupuncturist

- The Forgetting of Elvin Hayes & Education in Nicar...

- Passover--First Day--Hasids

- The Fifth Question

- Go, Cancer Bitch, Go

- My Most Useful Teaching Moment

- El Repliegue

- Two Miles

-

▼

April

(23)

Cancer Bitch recommends these links:

- Alternet.org

- As the Tumor Turns

- Being Cancer--its on-line book club discusssed my book.

- Big Grrls DO Cry: queer life meets precarious life

- Black Gyrl Cancer Slayer

- Breast Cancer Action

- breastcancer.org

- Chemo Chicks

- Chronic (Illness) Babe

- Code Pink women's peace group

- Collaborative on Health and the Environment

- Colon cancer cowgirl

- Earth Henna

- Friends of Cancer Bitch on Facebook

- Funny Cancer shirts and mugs

- Gayle Sulik, Pink Ribbon Blues

- Geezer Sisters (tho' only written by one of them)

- Get Real About Breast Cancer (w/ pic of Breast Cancer Barbie)

- Gilda's Club

- Goodbye to Boobs (by a pre-vivor)

- Humerus Cartoons

- I got the cancer (lymphoma)

- Mamawhelming

- Organic Consumers Assn.

- Our Bodies, Our Blog

- Paula Kamen

- Planet Cancer

- Recovery on Water

- S.L. Wisenberg/Red Fish Studio

- Skin Deep: un/safe cosmetic list

- Stacey Richter's Land of Pain

- Swimming in the Trees: author Jessica Handler of Atlanta

- Tara Ison

- Terry Tempest Williams

- The Assertive Cancer Patient

- The Cancer Culture Chronicles

- The Fifty-Foot Blogger, another denizen of Fancy Hospital

- Whirled News--better than the Onion

- Women & Children First bookstore

NOTATE BENE

Everything here is as accurate as I could make it. Occasionally I've changed identifying details when writing about others.

Links to audio and video

from my Farewell to My Left Breast party

taramosalata & other dips; photo by Vera Szabó

Farewell to My Left Breast Party

cream puffs, caprese; photo by Vera Szabó

April 12, 2007--The Making of the Mohawk

Don't try this at home. Uh, oh, we did.

The Mohawk Profile

L the Haircutter in Background

The Mohawk Demure

Finished.

Summer henna-wear

design by Jennifer Berman

Life after cancer, Budapest, July 2009

At medicinal baths, with testimonials from patients