Today I felt better as soon as I woke up, though I'd only slept about nine hours, and the night before I must have slept 13. And I can't define or delineate what is better. I still had and have the jittery, run-down-feeling headache. But it didn't bother me as much. How difficult it would be for a doctor to treat me. I'd say, I feel the same, except it was bad yesterday but not today, and I can't tell you how it's different. With this sort of headache, I feel the pain as dispersed pieces of glitter floating in my head, as suspended in gel. I could say amber, but it is more like gel, soft. And I feel I can't unfurrow my brow.

I was thinking yesterday about motivation and encouragement and I thought of the repliegue in Nicaragua in 1989. This is its definition, from La Barricada International , 1995: "an annual re-enactment of the Sandinistas' June '79 tactical retreat from Managua to Masaya." I couldn't have said it better. Even at the time, when people explained it to me, I knew it was a route the guerrillas took, and that two young people in particular had died (because their names were on the t-shirt I bought), but I was unclear about why it was being re-enacted and what exactly it had been. I should say "martyred" instead of "died" because that was the lingo. Young people who were alive were revolutionaries. If they were dead, they were martyrs, and local streets were named after them. Now I'm searching around the Internet to remind or educate myself, and see that it was not a retreat qua retreat that was being celebrated, but a strategic withdrawal, after which the revolutionaries came back to Managua in triumph. I was in Managua on the 10th anniversary of the revolution. I went because I wanted to figure out how the revolution was doing, and whose fault it was. Were its weaknesses due to the Sandinista leadership or to US support of the contras?

Of course, I never figured it out. I spent the summer teaching English to government health workers at the equivalent of the NIH, except it looked like a run-down elementary school with chickens in the yard. I was sick (though I didn't have parasites; I had that checked out) almost the whole time, and came back, my friend S said, almost too thin. I was so sick and weak that I decided not to go on the 19-km. repliegue. It was a Friday afternoon. Then I suddenly decided to join; I was lonely. I started walking and caught up with the march. I started talking to whoever I happened to be walking with. Somehow I found one of the few people I knew who was on the walk, this guy who had come to Nicaragua with the same volunteer program that I had. I joined him and his Nicaraguan host and we slept on the sidewalk in Masaya overnight. In the morning we took the bus home and my friend was pickpocketed. (Another volunteer in our program used to say that he felt like he was a tree that the Nicaraguans would pluck. This was true. They were master pickpocketers. On a crowded bus--the only kind--I lost a camera that was buried in my backpack. And I was cradling the backpack in front of me. I lost a small notebook that had the address of a woman I was going to exchange language lessons with. I never saw the notebook or the woman again. We Norteamericanos used to fantasize about placing mousetraps in our backpacks. I also used to fantasize about getting the pickpocketers on American TV; they could walk through the studio audience and impress everybody with their sleight of hand.) Well, we were there as volunteers, right? To give what was needed? So what was the problem? It was in Nicaragua that I also learned how to give graciously. I had some drawing paper that a friend said another friend would like to have. He said that instead of just leaving it for him, I should write a note. And I did. I also bought someone an entirely superfluous wedding present. I should have given her American money. I still cringe thinking about it.

What is the lesson for me, for my capitalista-individuista psyche about my experience on the repliegue? I didn't expect myself to join the march. No one expected me to. But because no one expected me to, I did. And I was fine. What does this say about motivation and walking when you're weak from chemo?

That if people tell me not to, it's easier to motivate myself? That I'm tougher than I think? I know that often if little is expected of me, I do very well.

Case two. Eight years before this, I was an intern at the Miami Herald. During the first week, an editor said I would need to learn to use the computers. He said, Oh, I'm sure you're a quick study. And I was.

Case three. The lovely and talented Itabari Njeri was doing a criminal justice series at the Miami Herald. She escaped to a fellowship, and I inherited the series. Her editor said to me, This will be great, unless you blow it.

I hated doing the reporting; one of the main sources smoked and littered while he drove. I was afraid I wouldn't write well. A senior reporter ending up helping me, and then I escaped too.

So in one case, there were no expectations, and I excelled. In the other, expectations were high, and I excelled. In the third, there were high expectations, expressed negatively, and I did not do well. What does this prove, Mr. Behavioral Scientist?

I try to lessen my students' anxiety. I say, I'm sure you'll do a good job. Does this help? And am I sure? Am I telling the truth?

It makes me mad to read in Groopman's book about experiments in which people with asthma are told they're getting a dose of albuterol, and then they're able to breathe easily despite being exposed to irritants. But of course, one of those doses of medicine is really saline. I hate being lied to. I hate people telling me asthma is psychosomatic. I hate the idea of people--even human guinea pigs who presumably signed the official forms that said, in essence, OK, lie to me--being lied to. But these were the experiments, as reported to Groopman. I know I keep hearing in my head the hearty voice of the chemo nurse on the phone: I'm sure you'll do great. She said that on two occasions before I asked her: Why do you think that? And she had a reason that I don't remember. Probably having to do with the improved anti-nausea drugs. And I haven't been very nauseated. Of course it is the first week. She said I might have heartburn and I have. She said I might have constipation and I haven't. Yet I know it strengthens me to hear that cheerful, confident voice in my head.

We want to predict the future. We want to know that we'll be safe and happy. People who pray build an image of how they want things to be. They exhort or implore the deity to bless and take care of ... and ... and .... This imagining is powerful and can change physiology. Yet a part of me fights against this. It's too too ... invisible.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

taramosalata & other dips; photo by Vera Szabó

cream puffs, caprese; photo by Vera Szabó

Don't try this at home. Uh, oh, we did.

L the Haircutter in Background

Finished.

design by Jennifer Berman

At medicinal baths, with testimonials from patients

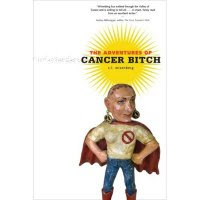

One Feminist's Report on Her Breast Cancer, Beginning with Semi-diagnosis and Continuing Beyond Chemo, w/ a side of polycythemia thrown in **You don't have to be Jewish to love Levy's rye bread, and you don't have to have cancer to read Cancer Bitch *** Cancer Bitch comes to you from S.L. (Sandi) Wisenberg in Chicago

Click on photo for Cancer Bitch reading/lecture schedule

Blog Archive

-

▼

2007

(192)

-

▼

April

(23)

- Cancer Bitch Behaves Badly Again

- Remembrance of Things Past or: Everybody's Got a W...

- A Cancer Bitch Behaving Badly

- Freedom and Development

- Notes on the Visible/Invisible

- Cancer is Boring

- Head Covering

- Men with Guns 2

- Men with Guns

- When It Falls, It Falls

- The End of Women and Children First???

- Briefly

- Hair is a Woman's Crowning Glory

- The Government Knows Much

- The Neighborhood Internist & An Embarrassment of G...

- The Neighborhood Acupuncturist

- The Forgetting of Elvin Hayes & Education in Nicar...

- Passover--First Day--Hasids

- The Fifth Question

- Go, Cancer Bitch, Go

- My Most Useful Teaching Moment

- El Repliegue

- Two Miles

-

▼

April

(23)

Cancer Bitch recommends these links:

- Alternet.org

- As the Tumor Turns

- Being Cancer--its on-line book club discusssed my book.

- Big Grrls DO Cry: queer life meets precarious life

- Black Gyrl Cancer Slayer

- Breast Cancer Action

- breastcancer.org

- Chemo Chicks

- Chronic (Illness) Babe

- Code Pink women's peace group

- Collaborative on Health and the Environment

- Colon cancer cowgirl

- Earth Henna

- Friends of Cancer Bitch on Facebook

- Funny Cancer shirts and mugs

- Gayle Sulik, Pink Ribbon Blues

- Geezer Sisters (tho' only written by one of them)

- Get Real About Breast Cancer (w/ pic of Breast Cancer Barbie)

- Gilda's Club

- Goodbye to Boobs (by a pre-vivor)

- Humerus Cartoons

- I got the cancer (lymphoma)

- Mamawhelming

- Organic Consumers Assn.

- Our Bodies, Our Blog

- Paula Kamen

- Planet Cancer

- Recovery on Water

- S.L. Wisenberg/Red Fish Studio

- Skin Deep: un/safe cosmetic list

- Stacey Richter's Land of Pain

- Swimming in the Trees: author Jessica Handler of Atlanta

- Tara Ison

- Terry Tempest Williams

- The Assertive Cancer Patient

- The Cancer Culture Chronicles

- The Fifty-Foot Blogger, another denizen of Fancy Hospital

- Whirled News--better than the Onion

- Women & Children First bookstore

NOTATE BENE

Everything here is as accurate as I could make it. Occasionally I've changed identifying details when writing about others.

Links to audio and video

from my Farewell to My Left Breast party

taramosalata & other dips; photo by Vera Szabó

Farewell to My Left Breast Party

cream puffs, caprese; photo by Vera Szabó

April 12, 2007--The Making of the Mohawk

Don't try this at home. Uh, oh, we did.

The Mohawk Profile

L the Haircutter in Background

The Mohawk Demure

Finished.

Summer henna-wear

design by Jennifer Berman

Life after cancer, Budapest, July 2009

At medicinal baths, with testimonials from patients