The things we know. The things we think we know. The things we feel we know. We were talking about Germany tonight. T's next book is about Germany. I thought he also said Europe, but L said he just said Germany. We were in a French restaurant. Butter instead of olive oil for the bread. I asked what he thought of the

Berlin Jewish Museum. What I thought of it: it was not designed for me. It is defensive. It is begging the visitor to remember, to learn, that Jews belonged in Germany, in Europe. That Jews were part of the history of Germany (however grim; however they were persecuted). My Berlin friend J had objected to the lack of class consciousness in the museum's exhibits. She also objected to the mentions of Christmas, but as we know, Anne Frank's family celebrated it, and in this book I've been reading,

Hitler's Exiles, there's repeated mention of it in the individual essays. Everyone is ripe to criticize museums; their public-ness, their please-come-and-visit-ness makes them especially prone to judgments. T said that the museum was trying to normalize Germany. I think this is what he said. I think he said that it was trying to explain the Holocaust as part of Germany's history. In the last room of the museum are eye-level cubes with color photos (note: the Holocaust is always presented in black and white; we think of it in black and white) of Jews in Germany today. We get a description and a quote. All proving: We are like you, o visitor from Europa. We are normal, just as you are normal. Is Germany normal? Not yet.

I talked about Jew-yearning, the people who feel Jewish or think they had a Jewish ancestor, or who know that their family had converted from Judaism. The little girl who spoke to her classmates about her

mishpacha and the other kids didn't understand, and so she learned that she was using the Yiddish word for

family. As an adult she converted. The way the German Jews (based on two examples) post their mezzuzahs inside their doors instead of outside because they're afraid. Yet the very recent trend of planting square engraved metal panels on the sidewalk in front of your apartment building, the squares with the names of family members who died in the Holocaust. Memorial squares right where you live. Very public. But not so completely public because there's no sure way to know which person in the building had this done. Though you could guess by comparing last names.

[She celebrated Christmas.]

[She celebrated Christmas.]The familiar and the unfamiliar. I remember Walter Abish's book,

How German Is It, which I read 25 years ago in grad school, and his questions about what is familiar. Objects can be so familiar that we don't delve into their meaning, or what's beneath them. So familiar that we can't see them as they are. When I was in San Francisco I tried to write descriptions of what I was seeing but the buildings were too familiar. San Francisco looked like San Francisco. I forced myself, as an exercise: in S's neighborhood, two- and three-story houses and apartment buildings, further apart and lighter-looking than the buildings in Berlin, more open to the street; you could walk up the steps to someone's door right off the street. The buildings were wood and stucco and cement, maybe, in pastel and other colors--gray-blue, maroon--sometimes muraled. There was a

painted lady at the end of her block. You could walk up to someone's window. But the main difference is the density. The buildings in Noe Valley housed one family or two. In front of many of the homes were lush little gardens: lemon trees, bougainvillea, roses, four-foot tall geraniums, ivy. Our geraniums here don't have a chance to grow that tall outside. Mission Street with its greengrocers and taqerias and dollar stores and abandoned old movie theaters--El Capitan, Tower, Latino. One movie theater, Victor Grand, just turned into a dollar store: Grand Opening. Narrow, deep little stores with hanging pinatas and cheap pairs of socks. Anything you could want or need.

What I love about the Bay Area is its self-indulgence combined with social earnestness:

I want my organic ice cream and I feel good that it comes in a biodegradable bowl. I deserve the goat cheese raspberry ice cream and I don't deserve it because over there on the sidewalk is a pile of rags that serves as someone's bed. It becomes defensive ambivalence.

The utmost indulgence, the laughable: a little shop that sells

smallbatch raw food for dogs and cats. Always the threat that the rug could be pulled out from under you:

This is an unreinforced masonry building. Unreinforced masonry buildings may be unsafe in the event of a major earthquake. Signs in windows in support of gay marriage, jobs in the Mission, the saving of the local firehouse.

Tonight we were in Chicago eating rich food cooked butter and lemon and talking about Germany. There's a deep part of me that feels I understand what it's like to be Jewish in Germany. Now. Maybe because of the pervasiveness of my guilt/shame (see two posts down), my defensiveness, my pride. OK, suppose I do. So what? What will I do with that?

***

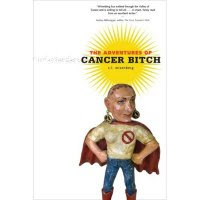

In case you're looking for cancer: Before dinner we went to a party and I was talking a long time with a stranger and when he asked what my newest book was about and I told him, I could see him looking looking at my chest. I was wearing a black tank top under a sleeveless white shirt and you could tell I just had one breast. I choose to make it obvious that I'm one-breasted and yet when someone stares and stares, keeping himself from asking what he wants to ask about the obvious, I feel self-conscious, invaded.

What are you looking at? Oh, I know what you're looking at and what troubles you is that you can't understand why I would go around with a flatness on one side. Maybe you even think it's indecent. Look at the result of the scourge of cancer. It's horrifying. But not strange. You can get used to it.

[Dubrovnik]

[Dubrovnik]