Last night I went to Women & Children First to hear Fatemeh Keshavarz speak about and read from her book, Jasmine and Stars: Reading More Than Lolita in Tehran. I went by myself and didn't know anyone. I wore my Bad Girls of Breast Cancer t-shirt and rode my bike from yoga. The program got a late start. Iranian-Americans (I presume) were milling around, mostly black-haired and speaking Persian/Farsi. Several had very black hair. I'd been told (in my hair days) that my hair was black but it was/is really dark brown. These women had black hair. I wondered for the first time if people can tell how dark my hair is from my disappearing eyebrows and my dark stubble. But let's talk about Iranians, Cancer Bitch. I'd been looking forward to the reading for weeks because I'd liked reading Reading Lolita in Tehran: A Memoir in Books by Azar Nafisi, but the more I thought about it, and talked to an Iranian activist about it at a rally, the more I suspected it. I'd come to the conclusion that it was so popular here, the darling of book groups, because it makes us feel good about American and English classics. That they matter. (And it appealed to book groups because it was about a book group, which was reading, perhaps, some of the classics the US groups had read.) For years American writers envied the Samizdat writers behind the Iron Curtain, because the forbidden word was powerful and sought-after. Popular. Relevant. (After the Wall came down, serious Eastern European literature became as irrelvant as American.) Here fewer and fewer people are reading and now here came a book that told us that Great Gatsby was important. It had LEGS. Iranians argued about it. Nafisi read our literature and reflected its relevance back to us. The relationship of Humbert Humbert to Lolita, she told us, was the same as the ayatollah's to Iranian women. They were objects, symbols, not known. I thought that was interesting. A thought I never would have come by on my own. I admit I read aloud her trial of Gatsby to a class I was teaching on Gatsby. How wonderful that people were arguing fervently about the novel. And it all came at a time when US intellectuals were criticizing their country. How bad could the US be, though, if it, and its loyal friend Britain exported great literature?

Keshavarz critiqued Nafisi's book on several counts. She accuses Nafisi of buying into stereotypes, of presenting the Oriental as the Other. She also criticized Nafisi for not talking about the US's role in placing and supporting the shahs. I feel a little loose here because I haven't read Keshavarz's book yet and I loaned out Nafisi's. Jasmine and Stars is a slim book, from a university press. I don't know how much play it will get. How much play do books get that criticize best-sellers? I don't know. Are they accused of riding on the coattails of what they criticize?

Part of what she read last night was of childhood, the lost world. That's become familiar to me from reading a few other Iranian-American memoirs. All seeming a bit too rosy by now. I talked to a woman afterwards who was telling me about the books written by Iranians still in Iran. What's been easy/attractive about reading the stories of Diaspora Iranians is that they are our guides. They bridge the strange with the familiar. Would it be easier or more difficult to enter in the Iranian-in-Iran world? I told this woman I was working on a Muslim-Jewish poetry anthology and later I asked her for titles of books in translation by Iranians. She named some Jewish books. I didn't have the presence of mind to tell her that I wasn't looking just for books by and about Iranian Jews. I didn't want to be perceived as narrow, but I also don't particularly want to read about Iranian Jews and hundreds of years of Iranian-Jewish history. I just am curious what writing from Iranians in Iran sounds like.

I asked Keshavarz a question that had been buzzing around in my head for a time: Why are there a number of memoirs by Iranian women in the Diaspora and so few by men? Are women writing more or do publishers perceive that their books will sell better, because they are the veiled, or would-be veiled? She didn't have a clear answer. But she said that women are writing a lot (the majority, maybe? of authors) in Iran and that they are the clear majority of university students. The literacy rate in Iran is 80-something percent, she said, and many American books are available in translation. It's not so isolated as Nafisi paints it.

It seemed that everyone in the audience knew one another. They all talked to one another after the reading, often in Persian/Farsi. I knew that I came to the reading with a different motivation and feeling than they had. I didn't have insider information. No one questioned my right to be there, or asked why I was interested in Iranian writing. I suppose I was strange enough in my bald head and Breast Cancer Action t-shirt. I guess the question is why there weren't more non-Iranians there. As there were when the Persepolis girl spoke about her graphic memoir. Which was an international sensation. Why it was is another question. Novelty, partly. Point of view, of a child looking at the revolution. Quality? Uniqueness? I bought it but haven't read much of it so I can't say yet.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

taramosalata & other dips; photo by Vera Szabó

cream puffs, caprese; photo by Vera Szabó

Don't try this at home. Uh, oh, we did.

L the Haircutter in Background

Finished.

design by Jennifer Berman

At medicinal baths, with testimonials from patients

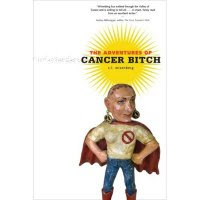

One Feminist's Report on Her Breast Cancer, Beginning with Semi-diagnosis and Continuing Beyond Chemo, w/ a side of polycythemia thrown in **You don't have to be Jewish to love Levy's rye bread, and you don't have to have cancer to read Cancer Bitch *** Cancer Bitch comes to you from S.L. (Sandi) Wisenberg in Chicago

Click on photo for Cancer Bitch reading/lecture schedule

Blog Archive

-

▼

2007

(192)

-

▼

May

(18)

- Lolita in Chicago

- Fancy O Fancy

- Post-Funeral

- The Blessing

- Funeral

- How Not to Be Intimidated

- Free Dinners & Free Dinners

- Foot, Horns, Feathers

- Cloak of Invisibility

- The Mothers

- The Watcher Watching Herself

- Cancer Bitch definitely on the air Thursday, May 10

- When the Obit is More Fun than the Front Page

- Bitches

- The Holter (Not Halter)

- Our Continent and Then Some

- At the Office of the County Assessor

- Barking, Berkeley, Hyde Park

-

▼

May

(18)

Cancer Bitch recommends these links:

- Alternet.org

- As the Tumor Turns

- Being Cancer--its on-line book club discusssed my book.

- Big Grrls DO Cry: queer life meets precarious life

- Black Gyrl Cancer Slayer

- Breast Cancer Action

- breastcancer.org

- Chemo Chicks

- Chronic (Illness) Babe

- Code Pink women's peace group

- Collaborative on Health and the Environment

- Colon cancer cowgirl

- Earth Henna

- Friends of Cancer Bitch on Facebook

- Funny Cancer shirts and mugs

- Gayle Sulik, Pink Ribbon Blues

- Geezer Sisters (tho' only written by one of them)

- Get Real About Breast Cancer (w/ pic of Breast Cancer Barbie)

- Gilda's Club

- Goodbye to Boobs (by a pre-vivor)

- Humerus Cartoons

- I got the cancer (lymphoma)

- Mamawhelming

- Organic Consumers Assn.

- Our Bodies, Our Blog

- Paula Kamen

- Planet Cancer

- Recovery on Water

- S.L. Wisenberg/Red Fish Studio

- Skin Deep: un/safe cosmetic list

- Stacey Richter's Land of Pain

- Swimming in the Trees: author Jessica Handler of Atlanta

- Tara Ison

- Terry Tempest Williams

- The Assertive Cancer Patient

- The Cancer Culture Chronicles

- The Fifty-Foot Blogger, another denizen of Fancy Hospital

- Whirled News--better than the Onion

- Women & Children First bookstore

NOTATE BENE

Everything here is as accurate as I could make it. Occasionally I've changed identifying details when writing about others.

Links to audio and video

from my Farewell to My Left Breast party

taramosalata & other dips; photo by Vera Szabó

Farewell to My Left Breast Party

cream puffs, caprese; photo by Vera Szabó

April 12, 2007--The Making of the Mohawk

Don't try this at home. Uh, oh, we did.

The Mohawk Profile

L the Haircutter in Background

The Mohawk Demure

Finished.

Summer henna-wear

design by Jennifer Berman

Life after cancer, Budapest, July 2009

At medicinal baths, with testimonials from patients