Monday on the subway going to chemo, I was re-reading Peter Gay's memoir, My German Question: Growing Up in Nazi Berlin, in preparation for hearing his lecture Tuesday at WRU (Well-Regarded University). A more accurate subtitle: Growing Up Jewish But Not Really Jewish in Berlin, and it Not Really Mattering Until the Nazis Made it Matter. Train stops, I shut the book, walk to the exit. A man standing there, looks at me and I'm thinking he's looking at my hat because clearly I'm bald underneath. He says, Auf Wiedersehen. I look at him and smile. Apparently he saw that the book was about Germany. It is about Germany, in a general and very particular way. Was he showing off his German? Was he German? He didn't look German. He was pudgy, maybe in his early 30s, with dark cropped hair. (Peter Gay's father didn't look Jewish; his non-Jewish business partner in Berlin didn't look German.) Gay's title is obviously a play on the term, The Jewish Question, which was asked all over Europe in the 19th century: Could the Jew be a European? The word "Jew" inot not appear on the cover of Gay's memoir. There's a picture of a Jew, Peter Israel Froelich, in a passport photo, stamped on April 21, 1939, when he was allowed to emigrate. The man on the L did not ask the Jewish Question. He did not ask any questions. He assumed. I assume he had no idea who Peter Gay is. (Gay changed from Froelich, "happy." The middle name Israel inserted by the Nazis.) I feel there are so many layers and layers of thought and history and life and assumption between what the guy on the subway said (one word!) and whatever response I could have given. The gap is huge. Or maybe not. I walked out the exit and up the stairs onto the street and toward hospital.

***

At chemo, the nurse asked if we'd heard about Virginia Tech. I'd heard vaguely, L hadn't yet. Several years ago some young Israeli soldiers came to the school I will call Catholic Conscience University to talk about why they refused to serve in the Occupied Territories. They were talking about how strange it was to be the U.S. One said something like this: If this were a university in Israel, you'd have metal detectors and soldiers at the gates and in all the buildings. And the audience laughed. I couldn't figure out, then, why they laughed and I still don't know. Because such measures seemed ludicrous? The young soldiers were bemused. Why are you laughing? they asked no one in particular, and no one answered. Some day there will be armed guards in hospitals and universities and we will shake our heads and think about the time when we had free access to so many places. I remember when stores didn't have security guards. Hell, I remember going to Foley's and Neiman-Marcus and Battlestein's in downtown Houston and just *telling* the clerk my parents' name and address, and being able to charge clothes. Some friends from Chicago remember going to the credit department in Marshall Field's and having the lady call home for permission to charge for a day.

***

Saturday we went to a memorial service for Ruth Young. She was the stepmother of our friend B, who lives in Berkeley. Ruth was managing editor of The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, editor of the women's literary magazine Primavera. She was married to Quentin Young, famous (in these parts) physician-activist. The service was star studded, in a Chicago kind of way. Studs Terkel was there, nearly 95, looking small and bent over and wearing his permanent red-checked shirt; legendary former Hyde Park alderman Leon Depres, 99, was there; and current Hyde Park alderman Toni Preckwinkle, and writers and activists and public hospital doctors and people I could pick out and people I couldn't. Later we were walking nearby and saw a street honoring Depres. He was independent in the Richard J. Daley days, which meant he was liberal and courageous. At the service, everyone talked about how Ruth could befriend children--not temporarily, but for years and years and change their lives. She sounds like she truly had the genius for friendship, which is an expression I've heard but never connected to anyone I knew. L and I knew her slightly. We had a few nice conversations with her when B came to Chicago. From Ruth we learned that the city Blue Bag recycling program doesn't work and therefore we lug our recycling to a private non-profit center about a mile away. We learned so much about her at the eulogy. She declared herself an atheist at 12 and never turned back. She was a tireless peace activist. But also an anonymous sender of flowers to a friend on her birthday ("from a secret admirer"), year after year, until her cover was blown. Then she stopped. Because of her, her husband gave his children gifts. Before her, he had told them on their birthdays: I gave you the gift of life.

She died of cancer. I tried not to think too much about myself and my new Mohawk, and to listen to the eulogies and to not wonder if people there didn't recognize me without my thick wavy hair. I know at least one acquaintance didn't. Ruth was extraordinary and in some ways I wanted her life and her attributes and her friends. Her friends and family described much honesty and conversation and arguments and questions and great food and drink. Who wouldn't want a life like that, while you were fighting the good fight? After the service, an 80-year-old cousin of the family started talking to us and looked at my hair and said, You're an artist, aren't you? You're making a statement. I didn't feel like saying, NO, I HAVE CANCER, so I said, Yeah, I'm a writer.

***

L and I walked around Hyde Park looking for hats and scarves. We stopped in a cafe. I heard two highschoolers talking about college applications. One boy said he received a fat envelople and two thin ones from the same medium-sized private university in New Jersey, which will be nameless here. He was so excited about the first one he called his mother at work. It was an acceptance, of course. And then he opened the second. It was a letter that said, Sorry, we admitted you by mistake. Then the third letter: You're on the wait list. And then, days later, he got a letter from the school chastising him for not responding to his acceptance by the deadline. How funny it would be if he declined in order to move himself up on the wait list.

***

While I was waiting to have my blood tested, pre-chemo, in the Cancer Center at Fancy Hospital, I saw two young men talking. One had a cane. They were both thin. The one with the cane said: You're insecure. You're a teacher. You're not appreciated. He said: You've led a whole lot of lives. This is not your first life. The other guy showed him the lines on his palm. They seemed to talk about life lines and heart lines. Then the cane guy talked about himself. He said that a woman (presumably a fortune-teller) told him, You should really enjoy your life now. He was upset. He thought that was rude. And then six months later he had a car accident. Two other people told him similar things. So he said, I don't have my hands read any more. I don't want to know.

We saw a movie about this the other week: First Snow.

My blood counts were fine. The oncologist seemed kind of bored at how fine I was. Not unhappy or rude but unsurprised. His Israeli sidekick wasn't there. I missed him. He was much more friendly and personable. But I don't need a friendly oncologist. Just one who answers my questions and whose poison will work.

Chemo was in a different room than last time. If you turned the lounge chair halfway around you could have a view of Lake Michigan. So there, cancer-sister in Marin County, you with your chemo view of Mt. Tamalpais. We have the lake! And buildings! Seeing nothing but nature out the window would make me nervous.

At the memorial service I was thinking, I don't want people to talk about me as a teacher or a friend. I want them to talk about my words.

Do I mean that?

*****

Before I left home for chemo on Monday there were about four listserv messages from an academic organization I belong to, Women in German, about German professors at Virginia Tech who may have been killed. I skipped over the messages and put them in the trash because the people didn't matter to me. I didn't know them. This morning the situation seemed more real and visceral as I've read and more. There's a note about someone's former student who definitely was killed. The image of a real person started to form in my head.

****

The first stop in Chemolandia was a room where I got my blood drawn. It was the first time I'd had it taken from the port in my chest and I had to wait. I was apprehensive because I'd read on-line how it could hurt to be poked there and that you should ask for a prescription for lidocaine. But the technichian assured me that a splash of "cold spray"would be enough, and it was. When she was through she said, in a spritely tone, I'm the meanest person you're going to see today.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

taramosalata & other dips; photo by Vera Szabó

cream puffs, caprese; photo by Vera Szabó

Don't try this at home. Uh, oh, we did.

L the Haircutter in Background

Finished.

design by Jennifer Berman

At medicinal baths, with testimonials from patients

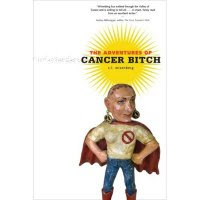

One Feminist's Report on Her Breast Cancer, Beginning with Semi-diagnosis and Continuing Beyond Chemo, w/ a side of polycythemia thrown in **You don't have to be Jewish to love Levy's rye bread, and you don't have to have cancer to read Cancer Bitch *** Cancer Bitch comes to you from S.L. (Sandi) Wisenberg in Chicago

Click on photo for Cancer Bitch reading/lecture schedule

Blog Archive

-

▼

2007

(192)

-

▼

April

(23)

- Cancer Bitch Behaves Badly Again

- Remembrance of Things Past or: Everybody's Got a W...

- A Cancer Bitch Behaving Badly

- Freedom and Development

- Notes on the Visible/Invisible

- Cancer is Boring

- Head Covering

- Men with Guns 2

- Men with Guns

- When It Falls, It Falls

- The End of Women and Children First???

- Briefly

- Hair is a Woman's Crowning Glory

- The Government Knows Much

- The Neighborhood Internist & An Embarrassment of G...

- The Neighborhood Acupuncturist

- The Forgetting of Elvin Hayes & Education in Nicar...

- Passover--First Day--Hasids

- The Fifth Question

- Go, Cancer Bitch, Go

- My Most Useful Teaching Moment

- El Repliegue

- Two Miles

-

▼

April

(23)

Cancer Bitch recommends these links:

- Alternet.org

- As the Tumor Turns

- Being Cancer--its on-line book club discusssed my book.

- Big Grrls DO Cry: queer life meets precarious life

- Black Gyrl Cancer Slayer

- Breast Cancer Action

- breastcancer.org

- Chemo Chicks

- Chronic (Illness) Babe

- Code Pink women's peace group

- Collaborative on Health and the Environment

- Colon cancer cowgirl

- Earth Henna

- Friends of Cancer Bitch on Facebook

- Funny Cancer shirts and mugs

- Gayle Sulik, Pink Ribbon Blues

- Geezer Sisters (tho' only written by one of them)

- Get Real About Breast Cancer (w/ pic of Breast Cancer Barbie)

- Gilda's Club

- Goodbye to Boobs (by a pre-vivor)

- Humerus Cartoons

- I got the cancer (lymphoma)

- Mamawhelming

- Organic Consumers Assn.

- Our Bodies, Our Blog

- Paula Kamen

- Planet Cancer

- Recovery on Water

- S.L. Wisenberg/Red Fish Studio

- Skin Deep: un/safe cosmetic list

- Stacey Richter's Land of Pain

- Swimming in the Trees: author Jessica Handler of Atlanta

- Tara Ison

- Terry Tempest Williams

- The Assertive Cancer Patient

- The Cancer Culture Chronicles

- The Fifty-Foot Blogger, another denizen of Fancy Hospital

- Whirled News--better than the Onion

- Women & Children First bookstore

NOTATE BENE

Everything here is as accurate as I could make it. Occasionally I've changed identifying details when writing about others.

Links to audio and video

from my Farewell to My Left Breast party

taramosalata & other dips; photo by Vera Szabó

Farewell to My Left Breast Party

cream puffs, caprese; photo by Vera Szabó

April 12, 2007--The Making of the Mohawk

Don't try this at home. Uh, oh, we did.

The Mohawk Profile

L the Haircutter in Background

The Mohawk Demure

Finished.

Summer henna-wear

design by Jennifer Berman

Life after cancer, Budapest, July 2009

At medicinal baths, with testimonials from patients