In Bathsheba's Breast I'm reading about William Halsted, the creator of the Halsted radical mastectomy at Johns Hopkins, and I suddenly remember that my great-grandmother's sister had cancer (breast?) and was treated at Johns Hopkins: a strange frisson of public and private. How to explain? That here's an outside reason, written in a book, for something that was private within the family. Each piece of information makes the other more real. How intent they must have been to get the very best treatment. I think about this for a few days. I have my cousin (the cancer patient's daughter) on tape from 1990 talking about moving up to Baltimore to be near her mother and not saying a word. Today I finally had time to listen to the tape. The time was probably the mid to late 1920s, and she moved in with her aunt and uncle and cousins in Baltimore. She was in seventh or eighth grade. Imagine a high-pitched Southern voice.

Cousin (who is my first cousin twice removed, my grandmother's generation): ...Mama went to Baltimore to see the doctor at Johns Hopkins. And she was there at the hospital and for two years I lived there, the most miserable two years of my life.

My father: Was she in the hospital for two years?

Cousin: Off and on. After she died I stayed on. Every time I wrote Papa a letter I said, I hate the M---s. I want to go home. And I don't blame them. I don't hold anything against them. They didn't know what to do with their own lives. The M---s knew nothing, absolutely nothing. They knew nothing about life. I never opened my—I didn’t talk to anybody. I remember sitting on the porch and S would say something. I needed somebody to talk to. I didn’t have anybody to talk to.

***

She remembered that the cousins lived across from Druid Park, and you could walk across the park to Johns Hopkins. As the tape goes on, she says that her mother did have cancer. So I was right about that. But throat cancer. She'd gone to New Orleans first for treatment then Baltimore. And she died, and her daughter stayed on, living with the cousins who didn't know anything about life. Whatever that means.

The four people on the tape--my cousin, her sister and brother-in-law, my father--are all dead.

The most recent death was my cousin's sister, at 97, in 2005. She was vibrant and blunt, had friends of all ages, especially lots of non-Jewish friends (a rarity in my family), played the piano, knitted her own clothes, had pierced ears. The last few years when I would go home, I would call to say hello and she would invite me to come over and pick out what I wanted of hers. I have some earrings, a German plate from her in-law's family, a silver pasta server. Her earrings are heavy, so I don't wear them too often. We do use the pasta handler (one of those claw-like things), and think about her when we use it. I don't understand the power invested in inherited things. I have my grandmother's carved hardwood table (because no one else needed a dining room table) and chairs and buffet, my other grandmother's stone-topped coffee table, desk and chairs, and a hokey painting of a boy and bearded man, presumably a bar mitzvah boy and grandfather, who wears a beatific and benevolent smile. It may be that same old thing: we think of them when we touch or see the objects, and we feel connected to the past, and we think about how the objects will survive us, and we hope go to someone who remembers us. In 1990 I went away for a year on a fellowship and gave my collection of dachshund figurines for safekeeping to a dachshund-addled friend. She asked later if she could have them if anything happened to me. I was glad to oblige. She had breast cancer about 10 years ago, had a lumpectomy and radiation and is fine.

Halted died in 1922, so he probably never saw my great-great-aunt. He was a pioneer of surgery, introducing rubber gloves to hospital practice, formalizing the medical residency program, advancing anesthesiology. He brought fame to Johns Hopkins, and so my great-great-aunt went there for the best treatment. When my father and his siblings were sick, his mother would take them on the train to New Orleans, the nearest big city, which was about three hours away. When I was diagnosed, my mother said she would go anywhere with me, to M.D. Anderson or the Mayo Clinic. I have a second opinion scheduled for tomorrow at Pretty Good Hospital, which is supposed to be Very Good at breast cancer treatment, and I am waiting to get an appointment with a fancy plastic surgeon who is Surgeon to the Stars (or at least public figures, according to his web site). The only hospital the surgeon works with is Pretty Good Hospital. He's not affiliated with any insurance companies, because, I presume, he doesn't have to be to in order to reel in the patients. L is appalled that I am actually thinking of switching hospitals, not just looking to confirm Fancy Hospital's recommended procedure. If you keep futzing around, he said last night, the cancer could go to your lymph nodes. This is the team that worked on W's breasts. I keep thinking of the breast photo album I looked at in the other plastic surgeon's office, and how he said the reconstructed breast doesn't look like a real breast, it's very round, like half an orange (I thought this; he didn't say it), and I want to know if that's true, or just true of the breasts he creates. I do have invasive cancer, but it seems less than aggressive, from what the surgeon told me. There was no urgency in her voice, like: We have to do this today. Here I was not long ago so sure I wouldn't have reconstruction at all, and now I'm wanting to have a Very Good-looking breast. Vanity, vanity.

(And I must add that I'm lucky to have fabulous health insurance from my husband L, and that my family was lucky that it could afford to go to the best places.)

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

taramosalata & other dips; photo by Vera Szabó

cream puffs, caprese; photo by Vera Szabó

Don't try this at home. Uh, oh, we did.

L the Haircutter in Background

Finished.

design by Jennifer Berman

At medicinal baths, with testimonials from patients

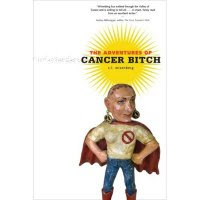

One Feminist's Report on Her Breast Cancer, Beginning with Semi-diagnosis and Continuing Beyond Chemo, w/ a side of polycythemia thrown in **You don't have to be Jewish to love Levy's rye bread, and you don't have to have cancer to read Cancer Bitch *** Cancer Bitch comes to you from S.L. (Sandi) Wisenberg in Chicago

Click on photo for Cancer Bitch reading/lecture schedule

Blog Archive

-

▼

2007

(192)

-

▼

February

(26)

- Stiff Upper Lip

- The Bad Girls of Cancer

- A Day in Which I Buy a Mastectomy Camisole & Fail ...

- A Nervous Laugher

- The Willy Loman of Female Diseases

- Lesser of Two Evils

- A Filling Without a Sandwich

- Thanks, Britney

- Gotta Date

- The Other Hand

- In the Office of the Plastic Surgeon to the Stars/...

- Lump in the Throat/Hail to Tricky Dickie/Marbles i...

- Confusion sets in

- Activism

- Public and private

- Doing well

- Driving to Distraction

- I Am Milked

- Benign!

- Telling

- Austro-Hungarian Empire/Breast Grid

- An aside: Today I am a Unitarian.

- Jews and Jesus, Death and Taxes

- Whodunnit

- Italian Folktales

- The Armenian Genocide

-

▼

February

(26)

Cancer Bitch recommends these links:

- Alternet.org

- As the Tumor Turns

- Being Cancer--its on-line book club discusssed my book.

- Big Grrls DO Cry: queer life meets precarious life

- Black Gyrl Cancer Slayer

- Breast Cancer Action

- breastcancer.org

- Chemo Chicks

- Chronic (Illness) Babe

- Code Pink women's peace group

- Collaborative on Health and the Environment

- Colon cancer cowgirl

- Earth Henna

- Friends of Cancer Bitch on Facebook

- Funny Cancer shirts and mugs

- Gayle Sulik, Pink Ribbon Blues

- Geezer Sisters (tho' only written by one of them)

- Get Real About Breast Cancer (w/ pic of Breast Cancer Barbie)

- Gilda's Club

- Goodbye to Boobs (by a pre-vivor)

- Humerus Cartoons

- I got the cancer (lymphoma)

- Mamawhelming

- Organic Consumers Assn.

- Our Bodies, Our Blog

- Paula Kamen

- Planet Cancer

- Recovery on Water

- S.L. Wisenberg/Red Fish Studio

- Skin Deep: un/safe cosmetic list

- Stacey Richter's Land of Pain

- Swimming in the Trees: author Jessica Handler of Atlanta

- Tara Ison

- Terry Tempest Williams

- The Assertive Cancer Patient

- The Cancer Culture Chronicles

- The Fifty-Foot Blogger, another denizen of Fancy Hospital

- Whirled News--better than the Onion

- Women & Children First bookstore

NOTATE BENE

Everything here is as accurate as I could make it. Occasionally I've changed identifying details when writing about others.

Links to audio and video

from my Farewell to My Left Breast party

taramosalata & other dips; photo by Vera Szabó

Farewell to My Left Breast Party

cream puffs, caprese; photo by Vera Szabó

April 12, 2007--The Making of the Mohawk

Don't try this at home. Uh, oh, we did.

The Mohawk Profile

L the Haircutter in Background

The Mohawk Demure

Finished.

Summer henna-wear

design by Jennifer Berman

Life after cancer, Budapest, July 2009

At medicinal baths, with testimonials from patients