A fine day. Fine as in penalty. As in you think that the secretary of state hasn't sent you your license plate renewal sticker and then you find it on Sunday and when you go to put it on the car on Monday, there's that orange envelope under the windshield wiper, saying you owe the city $50 because your license plate expired on Friday. (And it is secretary of state in Illinois and not the DMV; the secretary's name is on every driver's license and that is why the office is a stepping stone to governor, because of name recognition.)

And fine as in you drive the nine miles to the WRU library for a book to use in class on Thursday and the book isn't on the shelf and when you report it missing at circulation, the girl asks you if you had the right call number and if it was an oversized book, which means it would be shelved elsewhere, and you say, I'm sure, and it wasn't oversized, and you don't say, When were you born? Because I was probably using this library before then. And then you try to check out a possibly useful book that was next to where the desired book should have been, and she delivers the shocking news that your account is blocked because you owe $200. Which can't be. Because faculty don't get fines. So then the finance person comes out and you tell her you renewed everything on line, and she says you can renew books just twice now, not forever and ever, and now faculty are being fined, and that your Juno account wasn't accepting the overdue notices from the library. You decide it's time to use the cancer card, especially since she has a pink ribbon pin on. She says you look familiar and you say you remember talking to her about the Holocaust and you say but you tell her you used to look different, you had more hair, before you had a chemo cut. And she says, How are you? And you say fine, and don't even feel guilty for your calculated cancer insert. Because what is cancer good for if not to help you get out of paying fines? Maybe you would have returned the books if you hadn't been so wound up with chemotherapy. And your library account is quite tangled, because you have been using the library for 33 years, with some hiatuses, and your status has always been changing: undergraduate in journalism, alum, summer instructor, graduate instructor in journalism, visiting scholar in Women's Studies, visiting scholar in Gender Studies, graduate instructor in creative writing and year-round staff member.

And she gives you a break, letting you check out the book that was near the book you wanted, and processing an MIA report on the book you wanted, and telling you you need to return three books to the library (Help me help you, she says), which you will do on Thursday when you go to class. And alas, if you want this book you'll have to go to the public library downtown, and there it's often the case that the books are not on the shelf even though they haven't been checked out.

Of your overdue books, there is one on Israel, one on French and German Jews in the Enlightenment, and one on travels in 19th century Texas. They all have to do with Jews, you tell her. And they do, even though Jews aren't mentioned in the latter book. It would take too long to explain. Though you were about to, because it's interesting and you don't get a chance to talk about your research interests all that much.

And you have two books that have been sitting on your dining room table for a long long time and they belong to the public library of Chicago. This is why you buy books. And you think of the Grace Paley story, Wants, about a woman who is returning books to the library that are 18 years overdue, and she writes a check to cover her $32 in fines. "Immediately [the librarian] trusted me," Paley writes, "put my past behind her, wiped the record clean, which is just what most other municipal and/or state bureaucracies will not do." You decide to send a copy of the story to the financial librarian, because, after all, she has an English degree, which she earned from your division, the night school.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

taramosalata & other dips; photo by Vera Szabó

cream puffs, caprese; photo by Vera Szabó

Don't try this at home. Uh, oh, we did.

L the Haircutter in Background

Finished.

design by Jennifer Berman

At medicinal baths, with testimonials from patients

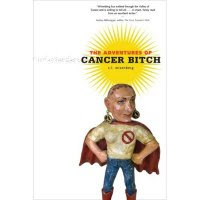

One Feminist's Report on Her Breast Cancer, Beginning with Semi-diagnosis and Continuing Beyond Chemo, w/ a side of polycythemia thrown in **You don't have to be Jewish to love Levy's rye bread, and you don't have to have cancer to read Cancer Bitch *** Cancer Bitch comes to you from S.L. (Sandi) Wisenberg in Chicago

Click on photo for Cancer Bitch reading/lecture schedule

Blog Archive

Cancer Bitch recommends these links:

- Alternet.org

- As the Tumor Turns

- Being Cancer--its on-line book club discusssed my book.

- Big Grrls DO Cry: queer life meets precarious life

- Black Gyrl Cancer Slayer

- Breast Cancer Action

- breastcancer.org

- Chemo Chicks

- Chronic (Illness) Babe

- Code Pink women's peace group

- Collaborative on Health and the Environment

- Colon cancer cowgirl

- Earth Henna

- Friends of Cancer Bitch on Facebook

- Funny Cancer shirts and mugs

- Gayle Sulik, Pink Ribbon Blues

- Geezer Sisters (tho' only written by one of them)

- Get Real About Breast Cancer (w/ pic of Breast Cancer Barbie)

- Gilda's Club

- Goodbye to Boobs (by a pre-vivor)

- Humerus Cartoons

- I got the cancer (lymphoma)

- Mamawhelming

- Organic Consumers Assn.

- Our Bodies, Our Blog

- Paula Kamen

- Planet Cancer

- Recovery on Water

- S.L. Wisenberg/Red Fish Studio

- Skin Deep: un/safe cosmetic list

- Stacey Richter's Land of Pain

- Swimming in the Trees: author Jessica Handler of Atlanta

- Tara Ison

- Terry Tempest Williams

- The Assertive Cancer Patient

- The Cancer Culture Chronicles

- The Fifty-Foot Blogger, another denizen of Fancy Hospital

- Whirled News--better than the Onion

- Women & Children First bookstore

NOTATE BENE

Everything here is as accurate as I could make it. Occasionally I've changed identifying details when writing about others.

Links to audio and video

from my Farewell to My Left Breast party

taramosalata & other dips; photo by Vera Szabó

Farewell to My Left Breast Party

cream puffs, caprese; photo by Vera Szabó

April 12, 2007--The Making of the Mohawk

Don't try this at home. Uh, oh, we did.

The Mohawk Profile

L the Haircutter in Background

The Mohawk Demure

Finished.

Summer henna-wear

design by Jennifer Berman

Life after cancer, Budapest, July 2009

At medicinal baths, with testimonials from patients